| Main | ||

| About | ||

| Implemented Projects | ||

| Future Prospective | ||

| Programs | ||

| membership |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Elements of effective collaboration between domestic violence advocates and health care providers through new curriculum in Post-Graduate Medicine Programs The goals of project was the creation new course by special program for licensing and re-certification for health care providers, development Domestic Violence Medical Resource Manual and develop an effective health resposponce to domestic violence. Training health care providers in 4 hospitals were most often apply victims. Organize round table with head of department of hospitals and discuss the way of implementation screening program. On the bases of project was created the post-graduate training course “Impact domestic violence on reproductive health“ is designed to be a companion peace to improving the health care response to domestic violence. Program grew out of the recognition that DV is widespread problem that has multiple, significant health consequences to victims. We created new course “Impact domestic violence on reproductive health “provide accessible information to health care providers in regarding the screening and treatment of patients who have experience domestic violence. The purpose of special course is to provide accessible information to health care providers in regards to advocacy and treatment of patients who have experience domestic violence. Because effective advocacy and treatment can only occur if the health care providers has a thorough understanding of the complex dynamics of DV, information regarding victim safety, power and control tactics and community resources. New course “ Impact domestic violence on reproductive health” was approved by the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs on 6 September 2006 as certificate program for postgraduate training for doctors, registration number of program N 2006001, duration training 5 days, fees which doctors pays for course $15, after accomplishment course doctors receive 25 credit scours (to receive permeation to work as doctor need during year to collect 75 credit scours). Five days training modules for health care practitioners who work in primary care, obstetric /gynecologist.  The manual cover the following topics:

MATERIALS OF TRAINING COURSEApprobation our program was held in 4 medical clinic and 133 doctors take part. Training packets containing lectures with extensive lecture notes, exercises for participants and pre- and post- tests for doctors . Also was published and distributed booklet “Impact Domestic Violence on Health -1000 sample A . DOMESTIC VIOLENCE -some of the characteristics that often accompany violence in intimate relationships:

Impact of Domestic Violence on healthWomen who are abused have poorer mental and physical health, more injuries and a greater need for medical resources than non-abused women. Health outcomes of DV has been associated with reproductive health risks and problems, chronic ailments, psychological consequences, injury and death (figure 2).

Reproductive health effectsWomen who experience intimate partner abuse are three times more likely to have a gynecological problems than are non-abused women. These problems include: chronic pelvic pain, vaginal bleeding or discharge, vaginal infection, painful menstruation, sexual dysfunction, pelvic inflammatory disease, painful intercourse, urinary tract infection, infertility. Sexual abuse can cause physical and mental trauma. In addition to damage to the urethra, vagina and anus, abuse can result in STIs, including HIV. Abuse limits women’s sexual and reproductive autonomy. Women who have been sexually abused are much more likely than non-abused women to use family planning clandestinely, to have had their pertner stop them from used family planning and to have a partner refuse to use a condom to prevent disease. Studies show that physical abuse occurs in approximately 4 to 15 percent of pregnancies in the USA, UK, Canada, Sweden, South Africa, Nicaragua. Abuse during pregnancy may be a more significant risk factor for pregnancy complications than other conditions for which pregnant women are routinely screened, such as hypertension and diabetes. Abuse during pregnancy has been linked with delays in obtaining prenatal care, increased smoking and drug/alcohol abuse, poor maternal weight gain and depression. Abuse of pregnant women is associated with unsafe abortion, miscarriage, stillbirth, low birth weight and neonatal mortality. Although it is difficult to determine a causal relationship between abuse and these adverse outcomes, a recent meta-analysis of 14 studies indicates a significant association between low birth weight and abuse during pregnancy. Research has found a four-fold increase in low birth weight among infants born to women who had been physically abused in pregnancy. Abuse may directly influence birth weight through, for example, blows to the abdomen precipitating premature labor. Indirectly, abuse is associated with factors also known to contribute to low birth weight, for example, smoking, alcohol and substance abuse, STIs, elevated stress level, poor nutrition.

Reproductive health -Risks and consequences of violence against women

Based on information from Population Reports (Heise, Ellsberg, and Gottemoeller 1999)

Why is this important for physicians?Health care providers can play a crucial role in detecting, referring and caring for women living with violence. Abused women often seek health care, even when they don’t disclose the violent event. Health care providers have the opportunity and the obligation to identify cases of abuse. For many women a visit to a health clinic for reproductive or child health services may be their only contact with the health care system. The health care sector can capitalize on this opportunity by ensuring a supportive and safe environment for clients, helping women receive the care they need. The acronym RADAR, developed by Massachusetts Medical Society, summarizes the steps physicians should take in diagnosing and treating victims of DV: R – Routinely ask about domestic violence

Ask about abuseAsking women about abuse in a direct interview can be an effective way to identify survivors of abuse. Nonetheless, few health practitioners routinely ask about abuse. In some programs, screening of all women may be impractical and even unethical if not done appropriately and confidentially. Screening of specific groups, such as women seeking prenatal care or other health services, may be feasible

When should you suspect, that a patient is a victim of Domestic Violence? Clues from the history:

Clues from the physical exam:

Clues from the partner’s behavior:

Screening for DV should be a routine part of the medical history. Providers must ensure a safe, confidential environment and establish a relationship of trust and respect for their clients prior to asking about abuse. Client waiting areas can offer educational materials, including posters on the walls and informational brochures, to let clients know that abuse can be discussed safely at the facility. Providers must be careful not to place clients at increased risk by violating their confidentiality. It is the provider’s role to empathize and validate clients’ experiences and to support their autonomy in deciding what to do about their situations (Figure 3).

What to ask:

The act of asking questions about violence can let women know that providers consider violence to be an important medical problem and not the client’s fault. Even if an abused woman doesn’t disclose the violence on a first visit, asking about it shows that the clinician cares and may encourage her to talk about it on a later visit. It is not enough to simply wait for women to dislose violence on their own. Experience has shown that many women are willing to talk about violence, but it is usually necessary for health personnel to take the initiative. Women are waiting for someone to knock on their door…

Document findingsCareful documentation of a woman’s symptoms or injuries, as well as of her history of abuse, are helpful for future medical follow-up. Documentation is also important in the event that she decides to press charges against the abuser or to seek custody of the children. Documentation should be as thorough as possible and clearly state the identity of the offender and his relationship to the victim. Photographs of injuries will be a big help too.

|

Primary amenorrhea |

No spontaneous menstruation by the end of age 18 |

1st degree amenorrhea |

Follicuiar maturation and estrogen production normal, no ovulation, no corpus luteum |

Hypogonadotropic amenorrhea |

Hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction, gonadotropins |

Normogonadotropic amenorrhea |

Mild hypothalamic-pituitary or uterine dysfunction, gonadotropins within normal limits |

Hypergonadotropic amenorrhea |

Ovarian dysfunction, gonadotropins elevated |

Physiologic amenorrhea |

Childhood, prepuberty, pregnancy, lactation, postmenopausal period |

Pathogenesis. The principal feature of primary amenorrhea due to hypothalamic dysfunction is hypogonadism. Demonstrable organic changes such as aneurysms, tumors, infections, or traumata are relatively rare; the etiology is very often ob-scure. Lesions incurred during embryonic development have been suggested. Psychological causes are infrequent, in contrast to secondary amenorrhea (see p 79), although they are an important factor in patients with anorexia nervosa or endogenous psychoses^ The picture may be further complicated by dysfunctions of other endocrine systems, such as hyper- and hypothyroidism, juvenile diabetes, or adrenogenital syndrome (see p 97).

Diagnosis. The clinical picture is that of hypogonadism, marked by underdeveloped breasts, hypoplastic genitalia, and paucity of pubic hair. Due to the lack of estrogen stimulation, there is little or no buildup of the vaginal epithelium. The gestagen test is negative, and the estrogen and gonadotropin levels are usually very low. The gonadotropin findings allow a clear differentiation from ovarian forms. In obvious cases the clomiphene test is always negative and the LH-RH test often so.

b) Central Disturbances

Pathogenesis. Emotional factors play perhaps the greatest role in the origin of secondary amenorrhea. Psychogenic conflicts of all types, familial and occupational stresses, tests, marital discord, sexual problems, fear of pregnancy, and changes of environment can all produce amenorrheal symptoms. A special case is anorexia nervosa, a psychoneurosis characterized by aversion to eating with consequent emaciation It is usually the result of environmental problems, especially as regards the patient's relationship to her parents. An equally dramatic form of psychogenic amenorrhea is pseudocyesis, or false pregnancy. Owing to an exaggerated fear of or longing for pregnancy, the patient develops all the subjective signs including substantial weight gain, the appearance of striae, breast enlargement, and the perception of fetal movements. Besides these psychoreactive forms, secondary amenorrhea may also occur in true psychoses and particularly in endogenous depression.

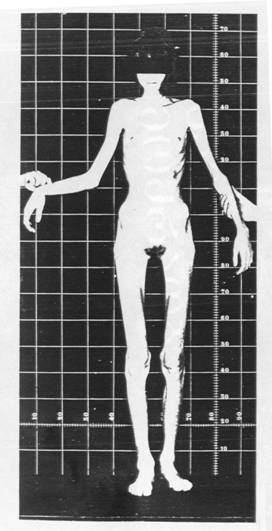

Extreme emaciation in anorexia nervosa (24 years)

A relatively common form of secondary amenorrhea is the “oversuppression syndrome” that may follow the use of oral contraceptives. It is caused by excessive central inhibition, which tends to occur mainly after the use of gestagen-base preparations and in women with antecedent menstrual irregularity. Organic changes in the CNS, such as inflammatory processes, tumors such as raniopharyngeomas, and cranial traumata are much less common causes of amenorrhea.

Diagnosis. The patient's history and clinical examination are of greatest importance. The basal temperature curve is always monophasic due to the absence of ovulation. Estrogen and gonadotropin levels are within or slightly below normal limits; the progesterone levels are always low. The gestagen test is usually positive, as are the clomiphene and LH-RH tests. Thyroid and adrenocortical function are normal, except in anorexia nervosa and organic changes in the region of the diencephalon.

d) Premature Menopause

Pathogenesis. The premature failure of ovulation before the age of 40 is not entirely uncommon. The etiology is unclear but may involve vascular processes linked to the genetic makeup. The course is essentially that of the normal climacteric, except that it occurs years prematurely: The periods first become irregular and theft cease altogether, accompanied by hot flushes and other deficiency symptoms.

Diagnosis. The early clinical findings are somewhat uncharacteristic, but the high level of gonadotropins and low estrogen values help to establish the diagnosis.

1. Deficiency Symptoms

Pathogenesis. The progressive decline of ovarian estrogen production during the climacteric and especially after menopause creates a "menopausai syndrome" in many women. It is also brought on by castration. The syndrome not only affects the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, but also leads to functional derangements of other autonomic centers in the diencephalon. Symptoms include irritability, headaches, forgetfulness, insomnia, and depression; but the most characteristic complaint is the hot flush, which occurs in over 80% of women. It takes the form of disturbing paroxysmal hyperemia of the face, neck, chest, and hands, accompanied by a sensation of heat and sweating. The pathogenic details are unclear but may involve regulation disturbances in the region of the cervical sympathicus. Circulatory symptoms include palpitation of the heart, vertigo, and tinnitus aurium (Table 9).

Besides disturbances of endocrine origin, menopausal women often experience psychological difficulties relating mainly to changes in living habits and to aging in general. Loss of the figure, children moving away or occupational problems may be precipitating factors.

One result of the estrogen deficiency, of course, is the occurrence of organic changes such as involution of the genital organs. Dyspareunia, senile vaginitis, and urethrocystitis are expressions of these changes. After menopause, senile osteoporosis develops much more frequently than in men. There also appears to be a link between estrogen deprivation and the obesity common in this age group, although lack of exercise and increased caloric intake are primarily responsible. In some circumstances the menopausal syndrome may considerably precede the menopausal event. The symptoms usually regress within a few years but occasionally persist to an advanced age. Both the duration and intensity of the syndrome depend strongly on the psychological makeup of the woman involved. Her education, environment, and degree of adjustment play a decisive role. Hormone assays are of little value, since subjective complaints generally are sufficient to establish the diagnosis, except in premature menopause, q. v. The gonadotropin levels are elevated and the estrogen levels reduced, but these bear no direct relation to the severity of symptoms.

Menopausal syndrome

a) Pre- and Perimenopausal Bleeding

Pathogenesis. As in juveniles , dysfunctional bleeding in climacteric women is usually the result of a persistent unruptured follicle. In such cases the follicle develops to the tertiary or vesicular stage (see p 7), but ovulation does not occur due to the inadequacy of hypothalamic regulation. The increasing estrogenic effect causes excessive endometrial proliferation, leading after several weeks to cystic glandular hyperplasia In very rare cases, a granulosa cell tumor may create the same situation (see p 94). When the estrogen level falls below that required to sustain the hyperplastic endometrium, varying degrees of bleeding occur, ranging from slight staining to severe hemorrhage that may persist for weeks.

Diagnosis. Hormone assays yield little information, though estrogen levels may be somewhat elevated. Since organic changes are present in over 20% of climacteric menometrorrhagia, fractional curettage should be performed in every case. In cystic glandular hyperplasia, curettage has both a diagnostic and therapeutic role. Abnormal bleeding tends to recur in approximately two-thirds of cases, which may then be treated hormonally after malignancy is excluded. Bleeding can be effectively controlled with orally active estrogen-gestagen preparations, e. g., three to five tablets Primosiston (Schering) daily for 10 days. This regimen provokes heavy withdrawal bleeding and thus serves as a "hormonal curettage." For long-term therapy, oral contraceptives with a high gestagen content are suitable, such as Eugynon (Schering) or Ovulen (Searle). Parenteral depot preparations are less suitable, because their prolonged hormonal activity may lead to sustained, heavy withdrawal bleeding.

b) Postmenopausal Bleeding

Pathogenesis. In most cases postmenopausal bleeding is the result of organic changes. It may also be caused by cystic glandular hyperplasia due to the long-term administration of estrogen-containing preparations with considerable endometrial activity. In rare cases the estrogen source is a follicle which matures postmenopausally or an ovarian neoplasm, notably a granulosa cell tumor or a theca cell tumor. These are estrogen-producing, usually unilateral, semimalignant tumors whose volume is highly variable; they may reach an enormous size, or may be only a few millimeters in diameter and thus difficult to locate.

Diagnosis. Curettage is always indicated in postmenopausal bleeding. Further investigations depend upon histologic findings. If cystic glandular hyperplasia is discovered, all estrogen-containing ointments and tablets must be withdrawn. Moderately elevated estrogen levels in the serum or urine accompanied by an abnormally low postmenopausal level of pituitary gonadotropins are indicative of a hormone-producing ovarian tumor. In doubtful cases the diagnosis is verified by laparoscopy.

Pathogenesis. Galactorrhea refers to the unilateral or bilateral secretion of milk outside the lactation period This occurs physiologically during pregnancy and sometimes for a short time after weaning. In some cases bilateral galactorrhea is also observed during the use of oral contraceptives and psycho-tropic drugs, as well as in cause is functional hyperprolactinemia or pituitary adenoma Unilateral galactorrhea may be associated with intraductal carcinoma; in such cases the secretion is often grayish in color, but may also be serous or bloody.

Pathogenesis

Diagnosis. On the one hand, the diagnosis must exclude local processes. This can be done by careful clinical examination and by mammography, galactoductogra-phy, or thermography; also, a smear should be prepared and examined histologi-cally. On the other hand, it is necessary to perform multiple prolactin determinations in order to rule out an endocrine disturbance. If values are elevated, a roentgenographic or tomographic survey of the sella turcica is indicated so that a prolactinoma, if present, can be recognized as early as possible.

According the plan was trained 133 doctors in 4 medical clinic. Training packets containing lectures with extensive lecture notes, exercises for participants and pre- and post- tests for doctors .

Round table was organized with the head of department of hospitals, key persons and discuss the way of implementation screening program. multidisciplinary approach and strategy for future collaboration

1000 sample of booklet “Impact Domestic Violence on Health “ were published

Round table discussion with head of department of hospitals, key persons Parliamentarians representatives with Ministry of Health and Social Affairs came to conclusion about strategy for future collaboration and necessarily of creation screening program and implementation in medical records.

| Main About Implemented Projects Future Prospective Programs Membership | ©1996-2006 |

Webmaster Levan Chkheidze |